Southern Province History

From a 2002 review by Archivists C. Daniel Crews and Richard W. Starbuck, capturing many of the themes in their 2002 church history With Courage for the Future: The Story of the Moravian Church, Southern Province:

This exhaustive, authoritative, resource on the Church can be purchased from our online bookstore.

The first attempt by the Moravian Church to establish itself in the English colonies in America was a failure. James Oglethorpe invited the Moravians to settle in his colony of Georgia, and the Moravians responded by sending a party to Savannah in 1735. Several insurmountable difficulties arose almost immediately. The natives to whom we wished to bring the gospel had moved too far into the interior to be effectively reached. The climate proved pernicious. The neighbors failed to understand the Moravians’ stand against violence when war broke out with nearby Spanish Catholic Florida. By 1740 the Moravians saw the wisdom of relocating and moved to William Penn’s colony of Pennsylvania, where the Northern Province of the Moravian Church in America was born.

Our permanent growth as the Moravian Church in America, Southern Province, began not as an isolated mission endeavor like St. Thomas or Greenland, but as “settlement congregations” for church members who were immigrating from earlier Moravian settlements in Pennsylvania or Europe. Of necessity, our goal of mission work came later in our history.

By 1750 the Moravian Church was quite well known in Great Britain. Just the previous year Parliament had declared us to be an “ancient Protestant Episcopal church,” giving it a legal status alongside the state Church of England. Among those who looked kindly upon the Moravians was John Carteret, the Earl of Granville. As the last remaining “Lord Proprietor” of the Carolina colonies, he offered to sell to the Moravians 100,000 acres of land from his vast Carolina holdings. Bishop August Gottlieb Spangenberg led an exploration party of Moravians and surveyors to the backcountry of North Carolina, finally arriving in December 1752 at a suitable site “on the three forks of Muddy Creek” — encompassing almost all of present-day Winston-Salem in Forsyth County. A total of 98,985 acres were surveyed off, and Spangenberg named the tract “Wachovia,” after an ancestral estate of Count Nicholas Ludwig von Zinzendorf’s. The deeds to Wachovia were signed in London on August 7, 1753. Just two months later, on October 8, 1753, the first colony of Brethren set out from Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. They arrived to begin the first settlement in Wachovia on November 17, 1753, and as they held their first lovefeast that evening they could hear wolves howling in the surrounding forests.

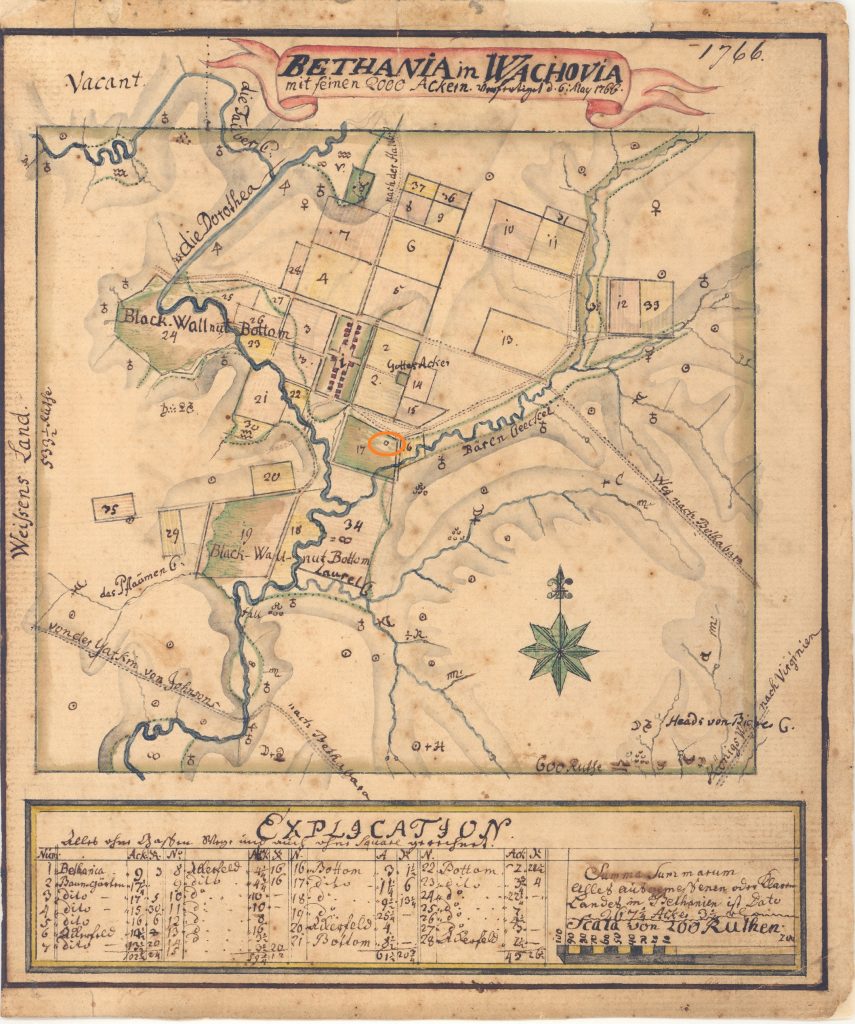

From the outset Wachovia’s first settlement was intended to remain a Unity farm, not a central city, and the name given to it reflects that intent: Bethabara, from the Hebrew meaning “House of Passage” (John 1:28, King James Version). However, progress was slow in carving from the wilderness other “villages of the Lord,” as Spangenberg envisioned them. On June 12, 1759, in the midst of the French and Indian War (Seven Years’ War), Spangenberg and other church leaders laid out Wachovia’s first planned community, Bethania, which the following April 13 was organized as a congregation of the Unity. Bethania was different from other Moravian settlement congregations. Eight refugee families petitioned to be a part of it, and so Bethania began as a mixed community of Moravians from Bethabara and “strangers” or newcomers to the Moravian Church.

Bethania’s Town Lot in 1766

Neither Bethabara nor Bethania was intended to be the central administrative community of Wachovia. That function was planned for a new community to be located in the heart of the Moravians’ Wachovia — Salem. The choice was made by use of the Lot, the prayerful reliance on the guidance of the Lord by the selection of a positive or negative Scripture verse. After several rejections, the Saviour designated the site for Salem on February 14, 1765. The Daily Text for that day was, “Let thine eye be opened toward this house night and day, even toward the place of which thou hast said, My name shall be there” (1 Kings 8:29). Work on Salem began in earnest with the felling of the first tree on January 6, 1766, a day so cold that medicines froze in their bottles at the apothecary’s shop in Bethabara. Unity administrator Frederic William Marshall and church surveyor Christian Gottlieb Reuter saw to the design of Salem — a broad main street with narrower side streets and a square in the center surrounded by the church buildings consisting of Gemein Haus, Brothers House, and community store. Later the Sisters House, Boys School, church building, and girls boarding school were also built around the square as Salem grew to be a substantial community. With the consecration of the Gemein Haus on November 13, 1771, the Festival of the Chief Elder in the Moravian Church, Salem was organized as a congregation. More than a century later it would come to be called Home Moravian Church.

Elsewhere in Wachovia, beyond Bethabara, Bethania, and Salem, other Moravian communities were begun. On the southern edge of Wachovia a number of families had settled, eager for the Lord’s word through the Moravian Church. At first only occasional visits could be made, beginning with Ludolph Bachhoff holding a little service “below the Ens” in the home of Adam Spach on November 27, 1759. A meeting house was constructed and opened with a lovefeast on March 11, 1769, and a “society” of worshipers was formed on February 4, 1770. Given the name Friedberg — hill of peace — the congregation was organized on April 4, 1773.

A number of English-speaking families — the rest of the Moravians spoke German — settled in southwestern Wachovia. Many of them had migrated from Maryland, where they had become acquainted with the Moravian Church or joined it at such preaching stations as Carroll’s Manor. On moving to Wachovia, they were eager to continue the association. The first English preachings among them were held in 1763, and interest grew until a meeting house was begun in 1775. The Hope congregation was organized on August 26, 1780.

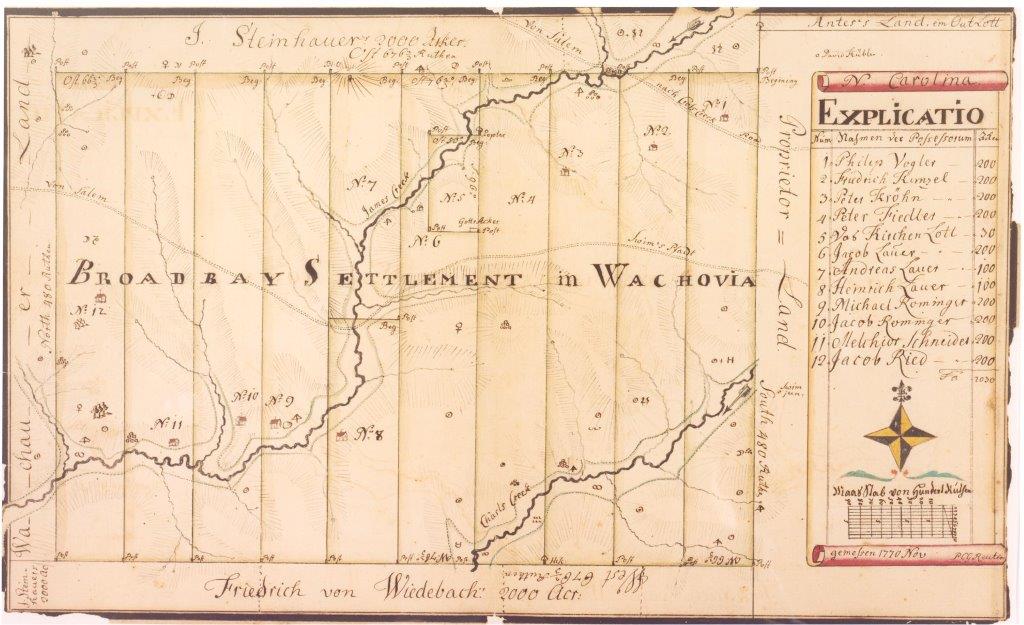

Settlement in southeastern Wachovia came in a roundabout way. German immigrants to the New World learned that the deeds to their property might be faulty. Besides, where they had settled — an area of coastal Maine called Broadbay — was proving too cold for their tastes. Their preacher, an itinerant Moravian minister named George Soelle, told them of the new endeavor in North Carolina and wrote to ask if they could come. Beginning in 1769 they began arriving in several companies, one group suffering shipwreck off the coast of Virginia. Land was set aside for these “Broadbayers” about five miles east of Salem, and a society was formed on July 21, 1771, with the name Friedland — land of peace. Work on a meeting house was far enough along on February 18, 1775, that Br. Tycho Nissen could move in as Friedland’s first minister. Finally on September 3, 1780, Friedland was organized as a congregation.

Friedland (“Broadbay”) settlement in 1770

From the arrival of the first settlers in 1753 until the organizing of Hope and Friedland in 1780 the Moravian Church in North Carolina had grown from 12 to 573 members, despite two wars that hindered even greater growth. But as the church in Europe continued to wrestle with debts left by the death in 1760 of Count Zinzendorf, the building of new congregations in Wachovia came to a standstill and stayed that way for the next three-quarters of a century.

Though the six Wachovia congregations — Bethabara, Bethania, Salem (Home), Friedberg, Hope, and Friedland — now grew only by natural increase in population, other work lay open. The early 19th century saw four foreign missions, a boarding school, one home mission, and the beginning of the Sunday school movement, which would sweep the Wachovia churches to farther fields.

An earnest desire of the Moravians in settling Wachovia was to bring the gospel to the natives of America. Wars initially prevented this endeavor, but by 1800 the time was right, and so on July 13, 1801, Brn. Abraham Steiner and Gottlieb Byhan occupied a little cabin at Springplace in today’s Murray County in northern Georgia. It was, Cherokee Chief John Ross declared many years later, “the first missionary school establishment in our Nation.” Through the labors of such devoted missionaries as John and Anna Rosina Kliest Gambold, Springplace and nearby Oochgelogy, begun in 1821, gained much influence and respect among the Cherokee, though the number of students and members remained small.

With the forced removal of the Cherokee along the “Trail of Tears,” Miles Vogler, Gottlieb Hermann Ruede, and Johann Renatus Schmidt also went west in 1838 and were greeted on October 27 by Cherokee Moravians at Barren Fork in the Indian Territory, now eastern Oklahoma. Other stations were established: Beattie’s Prairie (later renamed Canaan) in 1840 (destroyed in the Civil War), New Springplace at Spring Creek in 1842; Mount Zion in 1846 (destroyed in the Civil War), Woodmount in 1872, Mohr’s (later renamed Mount Zion) in 1886. Though opportunities for service were abundant — including preaching and teaching in the Cherokee capital of Tahlequah — the Wachovia administration back in North Carolina, 1,000 miles away, struggled to secure not only the finances but also the personnel to staff the missions. In 1892 the suggestion of the Unity Mission Board was accepted to transfer the Cherokee mission to the Northern Province. A new federal law in 1898 meant the farms at Woodmount and New Springplace could not be retained, making further work among the Cherokee impossible. The Moravians abandoned the endeavor in 1899. Three years later the Moravian Church asked the Danish Lutheran Church to assume responsibility for New Springplace, which by then was called Oaks, Oklahoma. On July 13, 2001, the Eben Ezer Lutheran Church in Oaks celebrated 200 years of mission to the Cherokee dating back to old Springplace in Georgia.

A second mission to natives was envisioned in the early 1800’s when Brn. Carsten Petersen and Christian Burkhardt left Salem on March 31, 1807, to open a station in the Creek nation. It took them a year and a half to established themselves at a trading post on the Flint River in west central Georgia. Illnesses beset the two, and then the War of 1812 snuffed out their efforts. They returned to Salem in 1813.

A third “mission” of the early 1800’s was hardly a stone’s throw from the Salem church at the foot of Church Street. At only its third meeting on February 10, 1822, the Salem Sisters’ Missionary Society vowed “the beginning of a mission among the Negroes in this neighborhood.” Mission veteran Abraham Steiner was called to oversee the new work, and on May 5, 1822, he announced “that a beginning of a small congregation of colored people was there,” consisting of three communicants. Through slavery, Civil War, emancipation, the congregation endured and grew, but it wasn’t until 1914 that it received a formal name. At its Christmas lovefeast on December 20 Bishop Edward Rondthaler called it St. Philips Moravian Church, the name the congregation is known by today.

St. Philips was not the only work among Africans. In 1844 services were scheduled every two weeks at the Bethania church, prompting the Ministers Conference to note by 1846 “the little negro congregation being formed” there. A church of their own was dedicated on October 6, 1850, and “about 60 blacks were present.” It was the beginning of what has grown to be Bethania African Methodist Episcopal Zion Church today.

Yet another mission opportunity arose in 1847 when missionaries were sent to northeastern Florida to minister to the slaves at Woodstock Mills, a plantation owned by a Mr. E.R. Alberti. “Various difficulties” arose, though, when Mr. Alberti insisted the missionaries tend only to the slaves’ spiritual condition and not their material plight. The mission was abandoned in 1853.

Responding to the earnest requests of neighbors, Salem at the onset of the 19th century opened a boarding school for girls, a rare educational opportunity for young ladies in those days. Samuel Kramsch began work as first inspector, or headmaster, on December 10, 1802, and though the first three students arrived on May 13, 1804, a school building for them on Salem Square was not opened until July 16, 1805. In later years, the boarding school, combined with the school for Salem’s own girls, begun in April 1772, grew to become Salem Academy and College today.

The home mission work of Wachovia began in the 1800’s at the inspiration of a layman. Br. Van Neman Zevely had been visiting the nearby mountains of Virginia when on November 11, 1835, the Brethren and Sisters of Salem formed a Home Mission Society to provide financial and spiritual support to church work in the region. Visits by Br. Zevely as well as such ministers as Henry A. Schultz, Samuel Thomas Pfohl, and Francis Florentine Hagen led directly to the organizing of Mount Bethel Moravian Church in Cana, Virginia, on November 25, 1852, followed by Willow Hill in Ararat, Virginia, on June 5, 1898, Grace in Mount Airy, North Carolina, on March 15, 1925, and Crooked Oak in Cana, whose church was consecrated July 17, 1927. Home mission work continues today under the auspices of the Provincial Board of Evangelism and Home Missions.

The flourishing new Sunday school movement proved to be another avenue of growth in the 1800’s despite Unity strictures on expansion. On September 8, 1816, two Salem Sisters traveled four miles south from town to a Lutheran church called Hopewell, where they opened a Sunday school. Hopewell remained Lutheran for more than a hundred years until it was purchased by the Southern Province and organized as a Moravian church on June 19, 1932. While Moravian churches — Friedland, Friedberg, Bethabara, Hope — began holding Sunday schools for their own children, other Sunday schools were opening in the Wachovia area. On November 29, 1835, Bethania’s minister, George Frederic Bahnson, preached at nearby Spanish Grove, which had been operating for a number of years. More than 100 years later, on January 6, 1929, Spanish Grove united with neighboring Olivet Sunday School, in a new church building to form Olivet Moravian Church. A Sunday school begun about five miles west of Salem was called New Philadelphia and — despite Unity restrictions on beginning new congregations — was organized on July 26, 1846. It was the first new congregation in the South since Hope and Friedland in 1780. A call from across the Yadkin River inspired Moravians to begin preaching in Davie County on September 16, 1854. Less than two years later, on May 24, 1856, the little church was consecrated and the congregation would receive the name Macedonia.

About the time of Macedonia’s beginning, the Unity finally abandoned all oversight of purely local administration and church growth. The General Synod of 1848 began the process, and the General Synod of 1857 concluded it. In Wachovia, truly administrative Synods were held (as opposed to Synods that were only “preparatory” to the General Synod in Europe) first in 1849, then adopting a constitution at the second Synod in 1856, and finally enacting the decentralizing wrought by the 1857 General Synod with the Synod of 1858 creating a Provincial Financial Board to advise the Provincial Elders Conference. With a flourishing mission to the Cherokee, fruitful work in the mountains of Virginia, two new churches close to home, the African mission in Salem on the verge of a building campaign, and a handful of thriving Sunday school stations, Wachovia was poised to take full advantage of the new local freedom granted by the Unity.

But growth did not occur, at least not immediately. The Civil War embroiled American Moravians for the first time in armed conflict with the blessing of the church. By the time peace returned four years later in 1865 freedom had been proclaimed to the African congregation in Salem but the church itself in the South was on the verge of bankruptcy. Slowly the church recovered, and slowly growth returned, much of it guided by two ministers, Christian Lewis Rights and Edward Rondthaler, who as successive presidents of PEC were eager for a rich harvest for the Lord. Kernersville, long a preaching station, was organized on November 10, 1867. Then in short order the seeds of the Sunday school movement began to sprout and blossom: East Salem (later called Fries Memorial) with its chapel consecrated on December 16, 1877; Olivet, which opened on December 22, 1878, near Spanish Grove; Providence (November 21, 1880) and Oak Grove (September 25, 1887) north of Salem; Calvary (April 20, 1893) in the county seat of Winston; Union Cross (August 13, 1893) east of Friedland; Wachovia Arbor (November 6, 1893; destroyed by fire December 26, 1989), Fulp (November 11, 1893), and Fairview (May 5, 1895) north of Salem; Mizpah (September 13, 1896) north of Bethania; Moravia (October 3, 1896) in Guilford County; Christ (October 25, 1896) in “west” Salem; Mayodan (November 29, 1896) up in Rockingham County; Enterprise (April 11, 1898) south of Friedberg; and Bethesda (October 22, 1899) 2 1/2 miles west of Salem.

As the 20th century was about to dawn, the Moravian Church in the South gained a new status within the Unity, in name which it already had held in fact. The General Synod of 1899 formalized the name Southern “Province”; before then, officially it was the Southern “District” of the overall American Province headquartered in Bethlehem, Pennsylvania. Administratively, though, the Southern churches had been independent of Bethlehem since 1771, when on a visitation Christian Gregor, Johannes Loretz, and Hans Christian Alexander von Schweinitz saw the wisdom of Wachovia reporting directly to Europe without having to go through Bethlehem. Use of the word “Province” had been commonplace since at least the forming of the “Provincial Helfer Conferenz ” in 1773.

Further growth continued in the Southern Province as the 20th century opened: Clemmons (August 13, 1900) and the Clemmons School, begun with a bequest of stagecoach operator E.T. Clemmons; Avalon (November 10, 1901; closed when the town burned June 15, 1911) near Mayodan; Greensboro (October 5, 1908, later called First Moravian Church of Greensboro); Trinity (July 14, 1912) in Salem’s Sunnyside; Immanuel (October 6, 1912; merged October 7, 2002 with New Eden to form Immanuel-New Eden) in Waughtown just southeast of Salem; and after the interruption of World War I Little Church on the Lane (November 7, 1920) in Charlotte; New Eden (January 28, 1923; now merged with Immanuel) also in Waughtown; Advent (June 22, 1924) two miles north of Friedberg; Ardmore (June 29, 1924) in Winston-Salem’s new western suburb; King (October 5, 1924) in southern Stokes County; Pine Chapel (November 16, 1924) in Salem’s Sunnyside; Houstonville (April 25, 1926; closed December 1944) in northern Iredell County; Leaksville (April 21, 1929) in Rockingham County; Rural Hall (May 3, 1931) just south of Stokes County; and the purchase of Hopewell Lutheran Church in 1932.

The Great Depression of the 1930’s forced a curtailment of church growth as did World War II, and when peace returned in 1945 expansion by the great Sunday school movement had pretty much run its course. In its place, two other forces for growth were driving the Southern Province onward. First, the young adults, those who had grown up in the Depression, fought a war, and were raising families of their own, were eager to put their energies to work within the church. Konnoak Hills (January 21, 1951) and Messiah (November 18, 1951) in Winston-Salem suburbs, and Raleigh (October 4, 1953) in the state capital are direct results of such youthful vigor. Then toward the end of the 1950’s in the wake of the Quincentennial celebrations, the Southern Province launched an ambitious church extension project into Florida. Coral Ridge (January 17, 1960) in Fort Lauderdale was the first, followed by Boca Raton (July 15, 1962), Rolling Hills (October 8, 1967) in Longwood, and Redeemer (March 23, 1975) in Winter Springs. While extension into Florida was going on, Charlotte, the largest city in North Carolina, got its second Moravian church, Park Road (November 24, 1963, later called Peace), and Community Fellowship (July 19, 1970) opened just south of Forsyth County in Arcadia, Davidson County.

In the 1970’s the Province’s Board of Homeland Missions (called the Board of Evangelism and Home Missions today) developed a plan to organize fellowships for Moravians living in communities where there was no Moravian church. They received regular visits from ministers and could grow into churches or not as circumstances dictated. First Church of Georgia (March 23, 1975) at Stone Mountain was the first church that arose from the fellowship plan. Other churches begun under this means of development were Covenant (February 12, 1978) of Wilmington on the coast; New Hope (February 13, 1983) in Newton near Hickory; and Redeemer (May 3, 1987; closed July 12, 1998) of Richmond, Virginia. At provisional church status is Morning Star (March 21, 1995) in Asheville. Still at fellowship status is Palmetto (1991) in Spartanburg, South Carolina.

While fostering churches from fellowships, the Southern Province also set about planting churches in fertile areas: Unity (November 16, 1980) in western Forsyth County; Good Shepherd (February 12, 1989), Kernersville’s second Moravian church; Christ the King (November 24, 1991) in Durham; and soon Holly Springs (charter opened September 15, 2001) in southwest Wake County; and New Beginnings (charter opened February 17, 2002) in Huntersville, North Carolina.

The venture into Florida, begun with such enthusiasm in the post Quincentennial 1950’s, began to fade as other denominations moved into the area. The first to close was Redeemer on June 14, 1981, followed by Coral Ridge on July 31, 1987, and Boca Raton on May 31, 1989. But far from a wasted effort, the endeavor into Florida proved a blessing in the 1980’s and ’90’s, not only for the Southern Province, but for the Moravian Church as a whole. From lands to the south streamed immigrants seeking the better opportunity and security that America offered, and some of these newcomers were Moravians who wanted to keep their faith and membership in their church. From Nicaragua and Honduras they came, Suriname and Guyana, Jamaica and the East West Indies (home of our earliest mission on St. Thomas in 1732). And the Moravian Church, Southern Province, was there to serve them. As yet (2002) only Prince of Peace (November 30, 1986) and New Hope (January 5, 1992) in Miami and Palm Beach (January 28, 1996) have reach organized church status, but waiting in the wings are King of Kings (provisional status March 21, 1993) in Miami, Suriname in Miami Beach (fellowship status June 1993), Tampa (fellowship status 1996), Sarasota (fellowship status June 1999), and New Covenant in Palm Beach, the newest fellowship as of 2002.

The Moravian Church came to the New World wilderness of North Carolina in the 1750’s in part for members to build a new home and a new life and still be Moravians. Today the Southern Province once again is offering the opportunity of a new home and a new life to Moravians coming from other lands. Mission work and service to neighbors continue as well as the Province reaches out to form fellowships that grow into full congregations in areas that did not have Moravians before. As the land was a wilderness then, so too our future may seem a wilderness today with doubts and cynicism, declining membership and financial uncertainties. And yet, as our spiritual pioneers did 250 years ago, we can rely on the firm foundation of our heritage, work together on the tasks given us today, and build to the future in the firm confidence of the sure leading of our redeeming Savior and Chief Elder of the Moravian Church.